Journalist Claire Robertson's fictional

debut comes in the form of the beautiful novel The Spiral House.

With ecchoes of Olive Schreiner and J M Coetzee, Robertson is

ambitious in her first attempt – and successful! Although I

struggled with the archaic language and style of writing in the

beginning of the book, I was sold to the story and determined to

finish it. I eventually got so enraptured in it that I could not put

it down.

The book is made up

of two parallel stories. The first story is set at the end of the

1700s and follows Katrijn van der Caab, a freed slave now working as

a wig-maker's apprentice. The story begins as Le Voir and Trijn go to

assist a client on the farm Vogelzang. The daughter of the house has

shamefully lost her hair, and Le Voir begins the slow work of making

the perfect wig for her, while Trijn joins the kitchen slaves in

their chores. On Vogelzang, which I believe means “birdsong”, the

mistress of the house is losing her mind, and only wants the company

of her caged birds. The master of the house fills his time with race

classification and experiements, and soon builds a bird cage of his

own, the spiral house.

The other story is

set in 1961 at a time when apartheid legislation was being enforced

in South Africa. We follow the nun Vergilius who practically raised

the black teenager Jacob. Her big hope for him is the change of

getting an education in Rome, but her letters seem not to reach their

destination. Vergilius has a streak of rebellion in her, and the only

thing keeping her at the convent is Jacob. But with the arrival of a

group of American travellers, things start to change for Vergilius.

Both Trijn and

Vergilius are in situations they have chosen to be, but where they

are not truly free. Trijn might be a free woman, but she does the

same work as the slaves at Vogelzang, and she is powerless in the

face of the white people who run the farm. This becomes clear when

the young mistress accuses Trijn of stealing, and Le Voir believes

her. Trijn realises that she is guilty because her word against the

mistress is worthless. Simillary, Vergilius' convent life consists of

strict routine where her every move is watched or heard. Her letters

are read before being sent out, and in this matter Vergilius

literally feels the censorship of the apartheid era (but in a

religious context).

Trijn has always

been conscious of her freedom, and what brings on a change for her is

circumstances at Vogelzang that she cannot ignore. The master's

spiral house holds a horrifying secret only Trijn has discovered, and

she decides that she is the only one who can do something to stop it.

She doesn't even fully disclose her secret to her romantic interest.

For Vergilius, on the other hand, the shift comes with the Americans.

While the rest of the South African population is clamping down,

through censorship, banning, physical intimidation, and legislation,

Vergilius actually comes out of her shell and decides to liberate

herself. And we learn that she is reading a book about a Trijn van

der Caab while she's doing it.

There is a lot of

symbolism in this book. The Vogelzang birds and their mad mistress

expressing censorship and imprisonment. Sex and virginity expressed

through how certain insects can get pregnant without a male. The loss

of hair as a symbol of lost innocence and possible promiscuity. And

as a backdrop the South African society that classifies you as less

based on your skin colour. While both stories are set in really dark

periods of South African history, they are full of hope.

Claire Robertson,

this could be the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

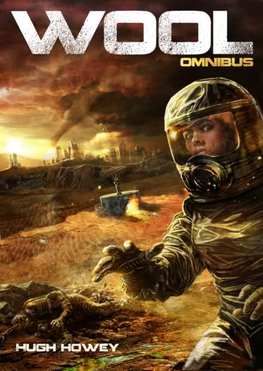

Oh,

and I cannot get enough of Joey Hi-Fi's cover designs. Once again he

has me pouring over his design to appreciate the beauty and

thoughtfulness that went into it. [He also made the cover design for

Lauren Beukes' Zoo City

and the new edition of Moxyland].